In the heart of Jerusalem, on the prestigious King George Street, stands the magnificent Heichal Shlomo building. This imposing building was constructed between 1953 and 1958 as the headquarters of the Orthodox Rabbinate of Israel (Rabbanut), which was founded in 1921. Today it houses the Herzog College, the Jewish Heritage Center and the Museum of Jewish Art.

The desire for a central place for the religious leadership of the Jewish people in Israel was expressed by the first Chief Rabbis, Rabbi Avraham Isaak Kook and Chacham Yaakov Meir, at the beginning of the 20th century during the British Mandate. 30 years later, in 1946, Rabbi Kook’s successor, Rabbi Yitzchak Eisik Herzog, purchased land on King George Street to establish the seat of the Rabbanut of the State of Israel.

However, some saw this as a renewed attempt to reestablish the Sanhedrin. This fear seemed to be shared by the “Brisker Rav”, Rabbi Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik, one of the leading figures of Lithuanian Orthodox Judaism in the 20th century, who called for a boycott of the project.

The Sanhedrin, a body of 71 Torah scholars, was the highest legal and rabbinical authority in Judaism’s legal system. It was established in the second year after the Exodus from Egypt at the command of Hashem and remained active until the destruction of the Second Temple. The seat of the Sanhedrin was the Lishkas HaGazis, one of the halls of the Temple.

In addition to its function as the highest legal authority, it was also responsible for setting the calendar (based on witness testimony about the sighting of the moon) and was also the highest authority on halachic questions (see Devarim chapter 17 verse 8). Only this body could decide and judge particularly serious cases such as “Navi Sheker” (a false prophet) and “Yir Hanidachas” (an entire city that served idolatry).

In some respects, the Sanhedrin was even above the Jewish king. For example, a Jewish king could not launch a war of conquest without first obtaining permission from the Sanhedrin (defensive wars did not require Sanhedrin approval).

With the destruction of the Second Temple, four years earlier to be exact (66 BC), the Sanhedrin was disbanded. Since then, however, there have been several attempts to reconstitute the Sanhedrin.

The first documented attempt took place as early as the time of the Gaonim (11th century). The Megilas Aviyatar, a parchment scroll from the Cairo Geniza, describes how Rabbi Eliyahu HaKohen Gaon, the head of the Yeshivat Gaon Jakov in Haifa, announced the restoration of the Sanhedrin. However, it seems to have been short-lived, as it is not mentioned in later historical sources.

One of the central issues surrounding the restoration of the Sanhedrin is the legitimacy of the “Semichah” (literally, the laying on of hands), the ordination of a rabbi with legal powers in modern times.

The Talmud states that only those who hold a semicha themselves may confer one. This ensures an uninterrupted tradition down to Moshe. In Tractate Sanhedrin (13b), Rabbi Yehuda Ben Bava is reported to have sacrificed his life in order to grant semicha to a number of students.

[In today’s rabbinical ordination, a teacher testifies that his student has the necessary knowledge to answer certain halakhic questions; this is not the “semicha” from the time of the Mishnah, which authorized a rabbi to impose fines].

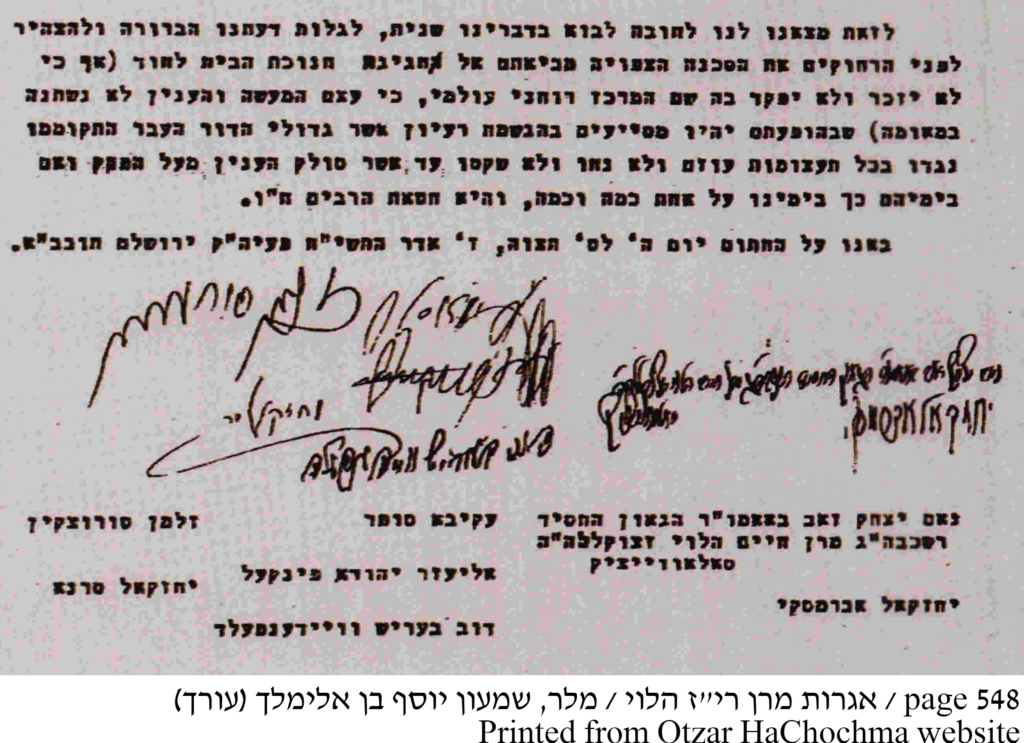

In the 16th century, attempts were made to reintroduce the semicha. This led to a heated debate among the scholars of the time. In 1538, the scholar Rabbi Yaakov Birav (abbreviated “Mahari Birav”, 1474-1541) initiated the return of the Semichah.

In his responsa Mahari Birav, he lays out the halachic foundations for the reintroduction of Semichah. It is based on the Rambam’s commentary on the Mishnah in Tractate Sanhedrin (Ch. 1, Mishnah 3). Maimonides writes that in his opinion it is possible to grant Semichah to a scholar with the approval of all the scholars in Israel. He adds that the Sanhedrin will be restored before the coming of Mashiach. On this basis, Rabbi Yaakov Birav was granted Semichah by 25 scholars of Zfas. This authorized Rabbi Yaakov Birav to grant Semicha to other scholars, and he used this newly acquired privilege to grant Semichah to four of his students, including Rabbi Yosef Karo, the author of the Shulchan Aruch.

However, this was met with severe criticism from the rabbis of Jerusalem. At the forefront was Rabbi Levi Ben Chaviv (abbreviated “Maharalbach”), Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem. In his opinion, the Rambam later changed his mind and in his legal code Mishneh Torah (Sanhedrin chapter 4, paragraph 11) doubted the possibility of issuing the Semichah with the approval of the scholars. Furthermore, the introduction of the Semichah would invalidate Hillel’s calendar, which, unlike the previous calendar, was based not on testimony but on mathematical calculations.

A fierce dispute broke out between the scholars of Zfat and Jerusalem, and in order to avoid disputes, the semichah was not continued (with the exception of Rabbi Yosef Karo, who also gave the semichah to his student, Rabbi Moshe Alschich).

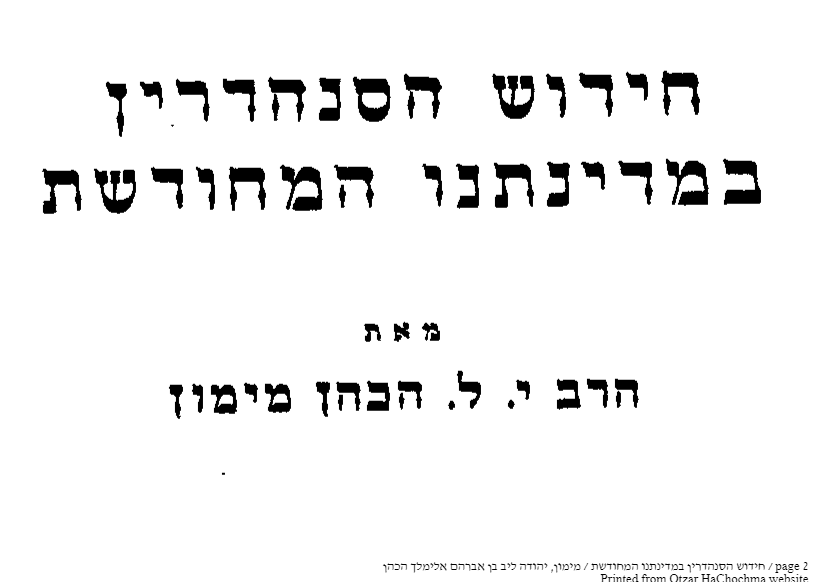

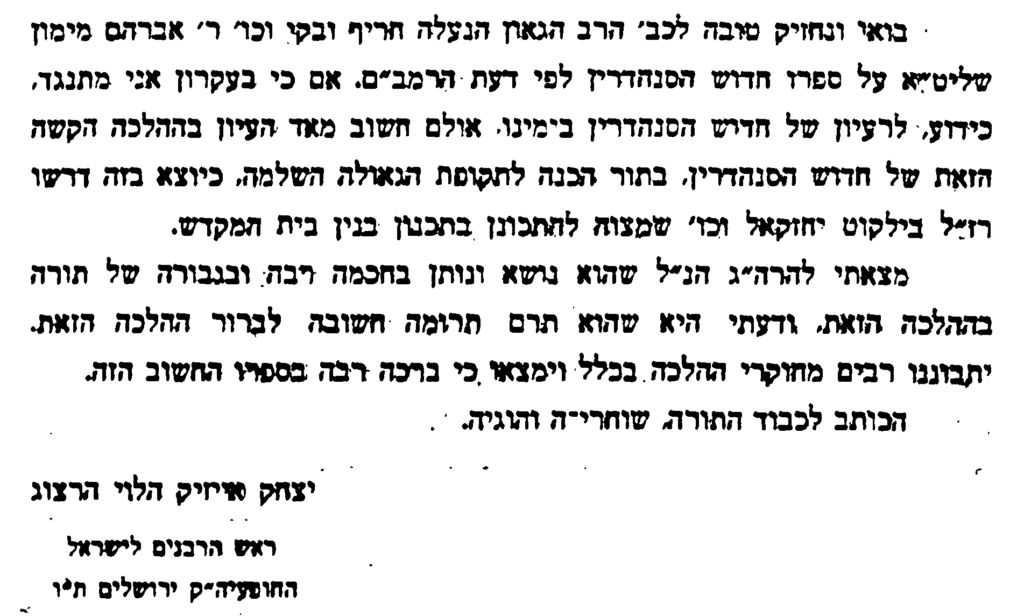

With the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the question of reinstating the Sanhedrin was raised again. One person who was particularly committed to this cause was Rabbi Yehuda Leib Maimon, the leader of the Mizrachi movement and the first Minister of Religion after the establishment of the State of Israel. He wrote a book entitled “Re-establishment of the Sanhedrin in our Newly Founded State“.

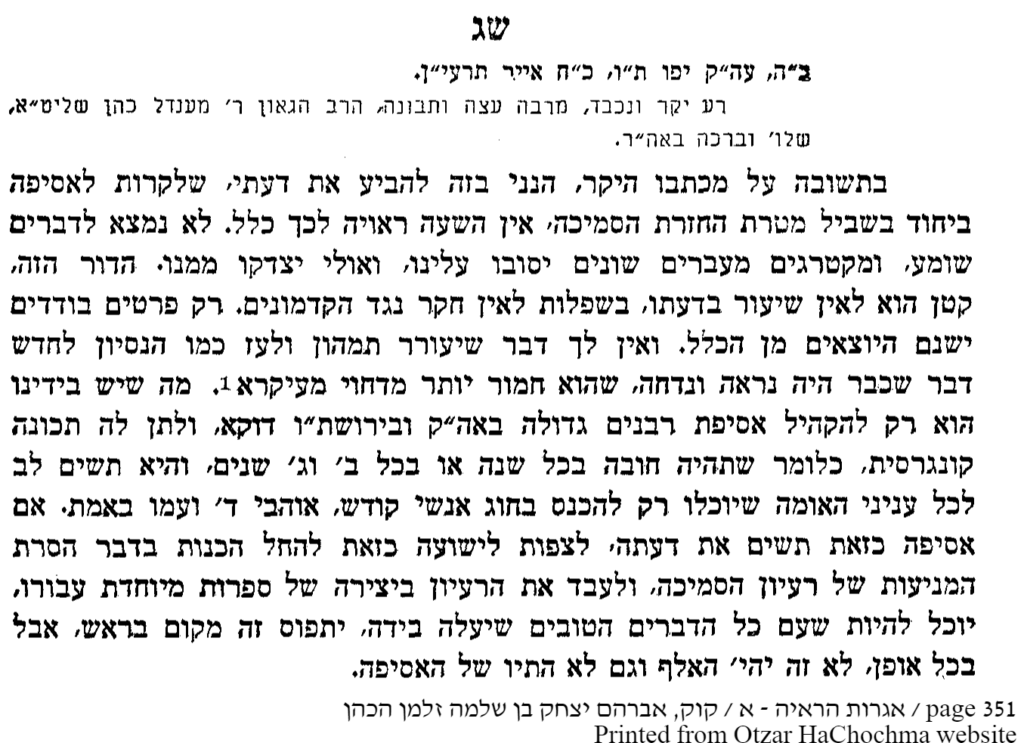

His mentor, Rabbi Kook, was skeptical about the reinstatement of the Sanhedrin (before the establishment of the State of Israel), although he considered Zionism and the return of the Jewish people to the Holy Land to be the beginning of redemption. In a letter to the Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv, Rabbi Zvi Makovski, in 1934, Rabbi Kook wrote that from a purely halachic point of view, it was possible to introduce the Semichah and establish a Sanhedrin. However, he doubted that there would be a consensus among the various Orthodox streams among the Jewish people and its leaders, and that a Sanhedrin would not be universally accepted. Nevertheless, he saw the institution of the Rabbanut as a kind of precursor and preparation for the Sanhedrin.

His successor, Rabbi Herzog, shared this fear and avoided supporting such an initiative.

The leaders of the Lithuanian movement, such as Rabbi Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik and Rabbi Avraham Yeshaya Kareliz (known as the “Chazon Ish”), categorically rejected the reintroduction of the Semichah and the Sanhedrin, primarily because they feared that they might be influenced by the secular government.

Since then, there have been repeated small attempts to establish a Sanhedrin, and some movements even claim to have established one, but none is recognized as such.

It seems that one must wait for the arrival of the Mashiach to re-establish the Semicha and the Sanhedrin. The Mashiach will have a Semichah so that he can grant semicha to others, and under his supervision it will undoubtedly be possible to form a Sanhedrin whose authority cannot be questioned. In any case, the seat of the future Sanhedrin will be in the Temple in the Lishkas HaGazis and not in the Heichal Shlomo.

Picture: Martin Vines, CC BY-SA 3.0 “Heichal Shlomo“