“We’re a computer company, not a fruit shop” Steve Wozniak (Co-Founder of Apple) reportedly joked when Steve Jobs proposed the name “Apple.” Since the founding of the American tech company, various theories and speculations have circulated about why the founders chose the apple as their namesake and why the apple in the logo had to be bitten.

Some saw it as a reference to the apple that allegedly fell on English scientist Isaac Newton’s head, inspiring him to discover the principle of gravity – a symbol of scientific breakthrough. [Actually Ronald Wayne’s, 3rd Co-Founder of Apple, draft from 1976 depicted Newton sitting under an apple tree.]

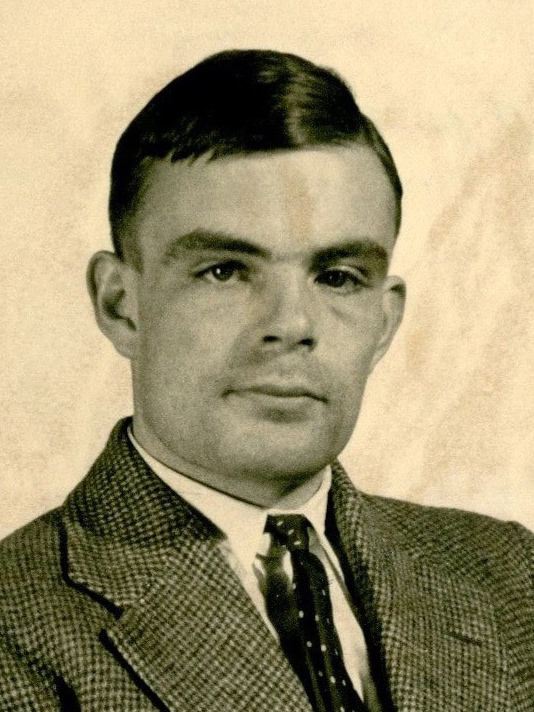

Others interpreted it as a tribute to Alan Turing, the “father of computer science and artificial intelligence,” who reportedly ended his life in 1954 with a poisoned apple.

The most well-known theory suggests that the bitten apple alludes to Adam and Eve’s sin of eating from the Tree of Knowledge despite Hashem´s prohibition. According to this interpretation, the apple symbolizes desire, freedom, and unlimited knowledge.

The true reason is (as often) less spectacular:

Steve Jobs chose the name “Apple” because he found the word “casual” and was experimenting with various fruit diets at the time. There’s also a simple explanation for the mysterious bite in the apple: Although Rob Janoff, the designer of the iconic Apple logo, liked the allusion to Alan Turing, he admitted in a 2009 interview that he wasn’t aware of Turing’s story at the time and simply wanted to avoid confusion with a cherry. After Janoff designed the logo, a colleague pointed out that the word “bite” was almost identical to the computer science unit “byte,” which Janoff described as a “happy little coincidence.”

The assumption that the “forbidden fruit” was an apple is widespread and was depicted as such by numerous Christian Renaissance artists (Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach) in the 16th century. John Milton also presented the forbidden fruit as an apple in Paradise Lost (1667).

“And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit, and did eat, and gave also to her husband with her; and he did eat.” (Bereshis Chapter 3, Verse 6)

In the Torah, despite the central role of this tree, we find no indication of which tree or fruit it was. The Torah merely describes it as “good for food,” “a delight to the eyes,” and “desired to make wise”.

However in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 70a), there is a dispute regarding which tree was involved in this fateful episode:

According to Rabbi Meir, the tree from which Adam ate was a grapevine, for nothing brings more lamentation upon mankind than wine. Rabbi Yehuda says it was wheat, reasoning that a child does not know how to say “father” and “mother” until it has tasted grain. Rabbi Nechemia maintains it was a fig tree, explaining that with the very means through which their downfall occurred, they were also remedied, as it is written: “and they sewed fig leaves together.” Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, 1040-1105) in in his commentary on the Torah (Bereshis Chapter 3, Verse 7) quotes only the opinion of Rabbi Nechemia that it was a fig.

It can be assumed that Michelangelo had at least heard of the latter opinion, as both apples and figs are depicted in the ceiling fresco of the Sistine Chapel (Temptation and Fall).

Maharal from Prague (Rabbi Yehuda Loew, 1520-1609) writes that the Jewish sages would not have engaged in discussion about which tree or fruit it was if there weren’t a lesson to be learned from it. He therefore presents a deeper explanation for this dispute:

Humans possess three drives that lead them to sin:

1. Lust/Desire

2. Ego

3. Ideology

The Maharal draws a parallel between these three characteristics, the three drives, and the three descriptions used by the Torah:

– “Good for food” corresponds to lust/desire, represented by figs

– “A delight to the eyes” corresponds to ideology, represented by wheat

– “Desirable to contemplate” corresponds to ego, represented by grapes/wine

[He provides detailed explanations for why these specific fruits correspond to these drives]

Thus, the true nature of this dispute is about which of these drives led to the original sin.

The Midrash (Bereshis Rabbah Chap.15, 7) additionally presents the opinion of Rabbi Abba from Akko, who suggests it was an Esrog (citrus fruit). Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) seems to follow this opinion in his Torah commentary (Vaikra Chap.23, 40). He adds that the Esrog in the Arbah Minim is meant to rectify the sin of Adam and Chava.

According to another Midrashic view, Chava pressed grapes and served Adam wine or grape juice. It’s not entirely clear whether this opinion aligns with Rabbi Meir’s view or represents a separate opinion.

Regarding Rabbi Yehuda’s identification of the “Tree of Knowledge” as wheat, the commentators explain that in the Garden of Eden, bread literally grew on trees (as it will again after the coming of the Mashiach). This interpretation aligns perfectly with the punishment, as it is written: “By the sweat of your brow shall you eat bread…” (Chapter 3, Verse 19).

It’s noteworthy that nowhere in Jewish sources is the apple explicitly suggested as a candidate for the forbidden fruit (although there might be a source in the Zohar indicating that it was an apple).

How did the apple come to be widely accepted as the forbidden fruit in popular belief?

A possible explanation lies in a linguistic confusion with the Latin word for “evil” in the Vulgate:

“Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil” (Bereshis Chapter 2, Verse 17) is translated in the Vulgata as “de ligno autem scientiae boni et măli.”

The word măli meaning “evil” is derived from the Latin word mălum. The Latin word for “apple” – mālum – is written and pronounced almost identically, making such a confusion quite plausible.

The Midrash presents a fifth opinion stating that Hashem has not and will not reveal to anyone which tree it was. Rambam (Rabbi Moses Maimonides, 1135-1204) in his philosophical work “Guide for the Perplexed” (Vol_2, Chap 30.25) appears to support this view.

In the Me’am Loez (Bereschis Chap. 2:17) Rabbi Yakov Kuli (1689-1723) explains that through this ambiguity, Hashem is teaching us that while one should recognize and repent for their sins, they should not become trapped in the past but rather focus on the future.